Parliament has become meaningless: Fazl

Muhammad Irfan Mughal Published October 17, 2025

|

| Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam chief Maulana Fazlur Rehman addresses the Mufti Mahmood Conference at Baisakhi Ground, Dera Ismail Khan, on Thursday. — Dawn |

Parliament has become meaningless: Fazl

Muhammad Irfan Mughal Published October 17, 2025

|

| Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam chief Maulana Fazlur Rehman addresses the Mufti Mahmood Conference at Baisakhi Ground, Dera Ismail Khan, on Thursday. — Dawn |

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya visited her alma mater, Delhi University’s Hindu College, during her maiden visit to India. She will hold significant meetings with External Affairs Minister C. Jaishankar and Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya returned to her alma mater in India on Thursday, as she visited Delhi University’s most prestigious Hindu College as an alumnus.

Her day-long visit to the college was filled with celebrations, cultural performances and long interactions, while sharing a deep bond between India and Sri Lanka. As a student of the Sociology department, Amarsuriya recalled her days in college 30 years ago, her classrooms and the north campus in the college.

This being her maiden visit to India after assuming charge as Sri Lanka's prime minister, Harini’s meetings with the top leaders will be on the lines of Sri Lanka’s India-first policy. According to highly placed sources, she will discuss in depth on attracting Indian investments to Sri Lanka. In a statement, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) said that her visit “will further strengthen the bonds of friendship, reinforced by India’s MAHASAGAR vision and its neighbourhood first policy.” Harini’s visit is also on the lines of regular high-level exchanges between the two countries and deep and multifaceted bilateral ties, according to MEA.

Amarasuriya, who is also Sri Lanka’s education minister, will visit IIT-Delhi and NITI Aayog to explore avenues of collaboration in education and technology. “This will be my first official visit to India as the prime minister of Sri Lanka. India and Sri Lanka are bound together by history, culture and shared values. Our relationship is one of great depth and importance, and I look forward to using this opportunity to strengthen our cooperation in every sphere, such as trade, investment, education, development and beyond.”

Sources in Sri Lanka say that Harini will have a friendly conversation with all the stakeholders in India to take home investments in various sectors, including power, education, infrastructure and many more.

Her visit comes exactly six months after Prime Minister Modi signed several important MoUs to strengthen the bilateral relationship between India and Sri Lanka in the areas of defence, maritime and other key sectors.

Though she is in Delhi to participate in NDTV’s World Summit, Amarasuriya will call on External Affairs Minister C.Jaishankar and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Her meetings with the external affairs minister and the prime minister assume significance as she has arrived in Delhi after her three-day visit to China, which concluded on October 15.

During her visit to Beijing, Amarasuriya attended the Global Leaders' Meeting on Women and met with the Chinese President Xi Jinping, Chinese Premier Li Qiang and China’s top political advisor Wang Huning.

During her China visit, she sounded positive on the Sri Lanka-China relations, while talking about the joint venture and collaborations between the two countries with regard to the Colombo port city, the Hambantota port and the central expressway, which are considered to be the centre of Sri Lanka’s growth strategy. She also lauded the commitment made by Xi to gender equality and women's empowerment globally during the opening ceremony of the Global Leaders' Meeting.

EAM Jaishankar meets Sri Lankan PM Harini Aamarasuriya in New Delhi

External Affairs Minister Dr S Jaishankar today met Prime Minister of Sri Lanka Dr Harini Aamarasuriya in New Delhi. In a social media post, Dr Jaishankar said that they discussed India’s continued support to Sri Lanka and strengthening the cooperation between the two countries in education and capacity building.

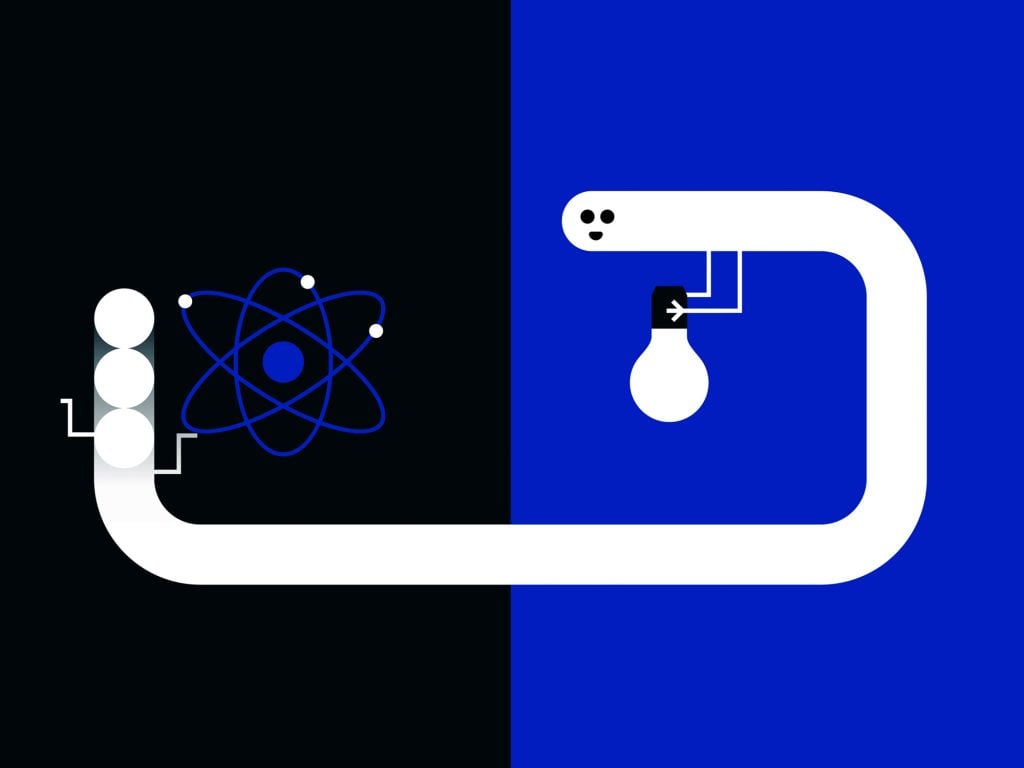

The Nobel Prize laureates in physics for 2025, John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis, used a series of experiments to demonstrate that the bizarre properties of the quantum world can be made concrete in a system big enough to be held in the hand. Their superconducting electrical system could tunnel from one state to another, as if it were passing straight through a wall. They also showed that the system absorbed and emitted energy in doses of specific sizes, just as predicted by quantum mechanics.

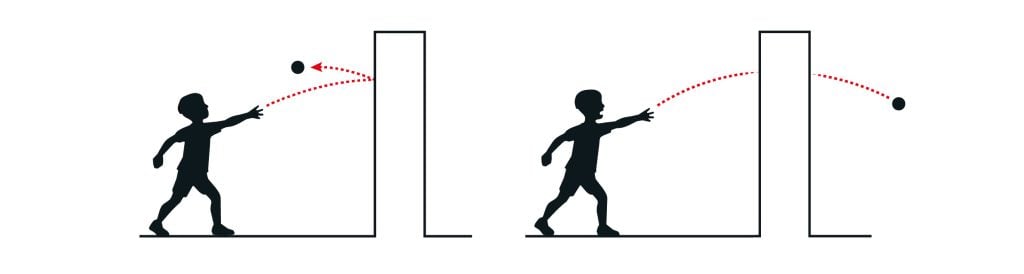

Quantum mechanics describes properties that are significant on a scale that involves single particles. In quantum physics, these phenomena are called microscopic, even when they are much smaller than can be seen using an optical microscope. This contrasts with macroscopic phenomena, which consist of a large number of particles. For example, an everyday ball is built up of an astronomical amount of molecules and displays no quantum mechanical effects. We know that the ball will bounce back every time it is thrown at a wall. A single particle, however, will sometimes pass straight through an equivalent barrier in its microscopic world and appear on the other side. This quantum mechanical phenomenon is called tunnelling.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics recognises experiments that demonstrated how quantum tunnelling can be observed on a macroscopic scale, involving many particles. In 1984 and 1985, John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis conducted a series of experiments at the University of California, Berkeley. They built an electrical circuit with two superconductors, components that can conduct a current without any electrical resistance. They separated these with a thin layer of material that did not conduct any current at all. In this experiment, they showed that they could control and investigate a phenomenon in which all the charged particles in the superconductor behave in unison, as if they are a single particle that fills the entire circuit.

This particle-like system is trapped in a state in which current flows without any voltage – a state from which it does not have enough energy to escape. In the experiment, the system shows its quantum character by using tunnelling to escape the zero-voltage state, generating an electrical voltage. The laureates were also able to show that the system is quantised, which means it only absorbs or emits energy in specific amounts.

To help them, the laureates had concepts and experimental tools that had been developed over decades. Together with the theory of relativity, quantum physics is the foundation of what has come to be called modern physics, and researchers have spent the last century exploring what it entails.

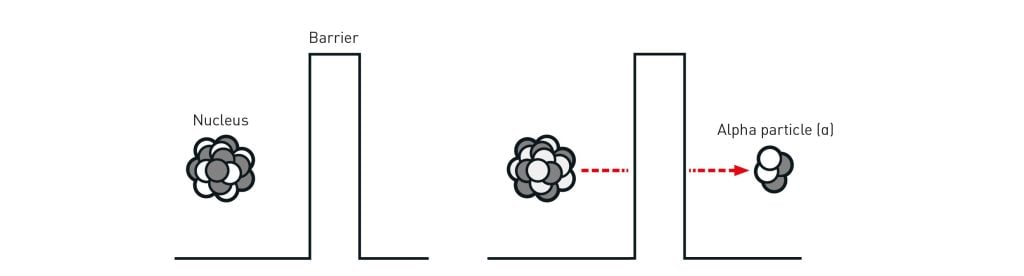

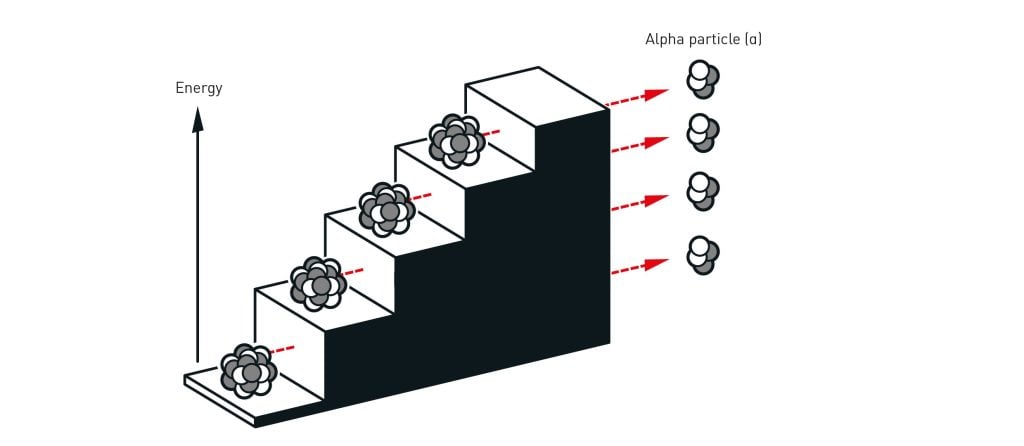

Individual particles’ ability to tunnel is well known. In 1928, the physicist George Gamow realised that tunnelling is the reason why some heavy atomic nuclei tend to decay in a particular manner. The interaction between the forces in the nucleus creates a barrier around it, holding in the particles it contains. However, despite this, a small piece of the atomic nucleus can sometimes split off, move outside the barrier and escape – leaving behind a nucleus that has been transformed into another element. Without tunnelling, this type of nuclear decay could not occur.

Tunnelling is a quantum mechanical process, which entails that chance plays a role. Some types of atomic nuclei have a tall, wide barrier, so it can take a long while for a piece of the nucleus to appear outside it, while other types decay more easily. If we only look at a single atom, we cannot predict when this will happen, but by watching the decay of a large number of nuclei of the same type, we can measure an expected time before tunnelling occurs. The most common way of describing this is through the concept of half-life, which is how long it takes for half the nuclei in a sample to decay.

Physicists were quick to wonder whether it would be possible to investigate a type of tunnelling that involves more than one particle at a time. One approach to new types of experiments originated in a phenomenon that arises when some materials get extremely cold.

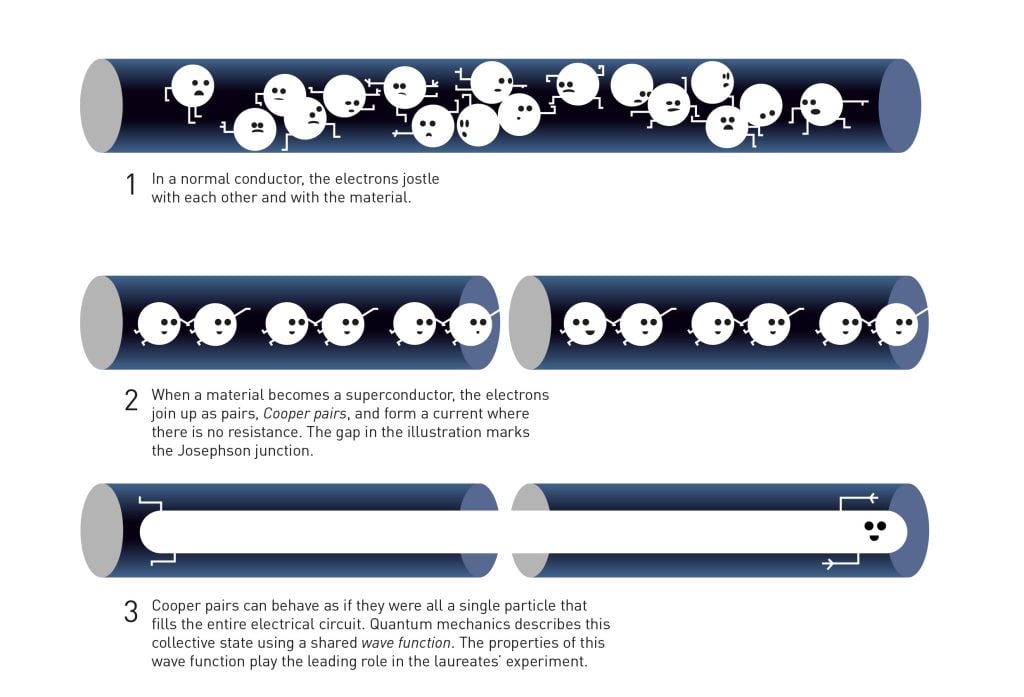

In an ordinary conductive material, current flows because there are electrons that are free to move through the entire material. In some materials, the individual electrons that push their way through the conductor may become organised, forming a synchronised dance that flows without any resistance. The material has become a superconductor and the electrons are joined together as pairs. These are called Cooper pairs, after Leon Cooper who, along with John Bardeen and Robert Schrieffer, provided a detailed description of how superconductors work (Nobel Prize in Physics 1972).

Cooper pairs behave completely differently to ordinary electrons. Electrons have a great deal of integrity and like to stay at a distance from each other – two electrons cannot be in the same place if they have the same properties. We can see this in an atom, for example, where the electrons divide themselves into different energy levels, called shells. However, when the electrons in a superconductor join up as pairs, they lose a bit of their individuality; while two separate electrons are always distinct, two Cooper pairs can be exactly the same. This means the Cooper pairs in a superconductor can be described as a single unit, one quantum mechanical system. In the language of quantum mechanics, they are then described as a single wave function. This wave function describes the probability of observing the system in a given state and with given properties.

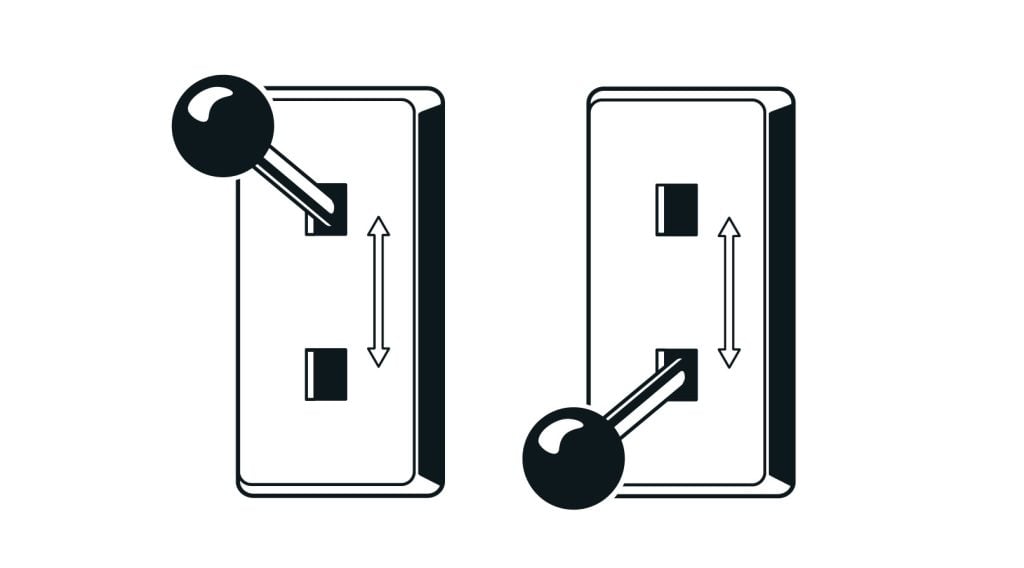

If two superconductors are joined together with a thin insulating barrier between them, it creates a Josephson junction. This component is named after Brian Josephson, who performed quantum mechanical calculations for the junction. He discovered that interesting phenomena arise when the wave functions on each side of the junction are considered (Nobel Prize in Physics 1973). The Josephson junction rapidly found areas of application, including in precise measurements of fundamental physical constants and magnetic fields.

The construction also provided tools for exploring the fundamentals of quantum physics in a new way. One person who did so was Anthony Leggett (Nobel Prize in Physics 2003), whose theoretical work on macroscopic quantum tunnelling at a Josephson junction inspired new types of experiments.

These subjects were a perfect match for John Clarke’s research interests. He was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in the US, where he had moved after completing his doctoral degree at the University of Cambridge, UK, in 1968. At UC Berkeley he built up his research group and specialised in exploring a range of phenomena using superconductors and the Josephson junction.

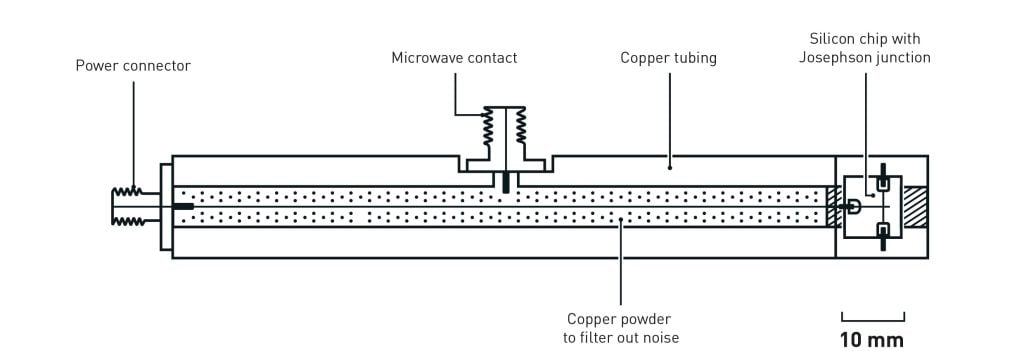

By the mid-1980s, Michel Devoret had joined John Clarke’s research group as a postdoc, after receiving his doctorate in Paris. This group also included the doctoral student John Martinis. Together, they took on the challenge of demonstrating macroscopic quantum tunnelling. Vast amounts of care and precision were necessary to screen the experimental setup from all the interference that could affect it. They succeeded in refining and measuring all the properties of their electrical circuit, allowing them to understand it in detail.

To measure the quantum phenomena, they fed a weak current into the Josephson junction and measured the voltage, which is related to the electrical resistance in the circuit. The voltage over the Josephson junction was initially zero, as expected. This is because the wave function for the system is enclosed in a state that does not allow a voltage to arise. Then they studied how long it took for the system to tunnel out of this state, causing a voltage. Because quantum mechanics entails an element of chance, they took numerous measurements and plotted their results as graphs, from which they could read the duration of the zero-voltage state. This is similar to how measurements of the half-lives of atomic nuclei are based on statistics of numerous instances of decay.

The tunnelling demonstrates how the experimental setup’s Cooper pairs, in their synchronised dance, behave like a single giant particle. The researchers obtained further confirmation of this when they saw that the system had quantised energy levels. Quantum mechanics was named after the observation that the energy in microscopic processes is divided into separate packages, quanta. The laureates introduced microwaves of varying wavelengths into the zero-voltage state. Some of these were absorbed, and the system then moved to a higher energy level. This showed that the zero-voltage state had a shorter duration when the system contained more energy – which is exactly what quantum mechanics predicts. A microscopic particle shut behind a barrier functions in the same way.

This experiment has consequences for the understanding of quantum mechanics. Other types of quantum mechanical effects that are demonstrated on the macroscopic scale are composed of many tiny individual pieces and their separate quantum properties. The microscopic components are then combined to cause macroscopic phenomena such as lasers, superconductors and superfluid liquids. However, this experiment instead created a macroscopic effect – a measurable voltage – from a state that is in itself macroscopic, in the form of a common wave function for vast numbers of particles.

Theorists like Anthony Leggett have compared the laureates’ macroscopic quantum system with Erwin Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment featuring a cat in a box, where the cat would be both alive and dead if we did not look inside. (Erwin Schrödinger received the Nobel Prize in Physics 1933.) The intention of his thought experiment was to show the absurdity of this situation, because the special properties of quantum mechanics are often erased at a macroscopic scale. The quantum properties of an entire cat cannot be demonstrated in a laboratory experiment.

However, Legget has argued that the series of experiments conducted by John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis showed that there are phenomena that involve vast numbers of particles which together behave just as quantum mechanics predicts. The macroscopic system that consists of many Cooper pairs is still many orders of magnitude smaller than a kitten – but because the experiment measures the quantum mechanical properties that apply to the system as a whole, for a quantum physicist it is fairly similar to Schrödinger’s imaginary cat.

This type of macroscopic quantum state offers new potential for experiments using the phenomena that govern the microscopic world of particles. It can be regarded as a form of artificial atom on a large scale – an atom with cables and sockets that can be connected into new test set-ups or utilised in new quantum technology. For example, artificial atoms are used to simulate other quantum systems and aid in understanding them.

Another example is the quantum computer experiment subsequently performed by Martinis, in which he utilised exactly the energy quantisation that he and the other two laureates had demonstrated. He used a circuit with quantised states as information-bearing units – a quantum bit. The lowest energy state and the first step upward functioned as zero and one, respectively. Superconducting circuits are one of the techniques being explored in attempts to construct a future quantum computer.

This year’s laureates have thus contributed to both practical benefit in physics laboratories and to providing new information for the theoretical understanding of our physical world.

Additional information on this year’s prizes, including a scientific background in English, is available on the website of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, www.kva.se, and at www.nobelprize.org, where you can watch video from the press conferences, the Nobel Prize lectures and more. Information on exhibitions and activities related to the Nobel Prizes and the prize in economic sciences is available at www.nobelprizemuseum.se.

JOHN CLARKE

Born 1942 in Cambridge, UK. PhD 1968 from University of Cambridge, UK. Professor at University of California, Berkeley, USA.

MICHEL H. DEVORET

Born 1953 in Paris, France. PhD 1982 from Paris-Sud University, France. Professor at Yale University, New Haven, CT and University of California, Santa Barbara, USA.

JOHN M. MARTINIS

Born 1958. PhD 1987 from University of Californa, Berkeley, USA. Professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, USA and Chief Technology Officer at Qolab, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

“for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit”

Science Editors: Ulf Danielsson, Göran Johansson and Eva Lindroth, the Nobel Committee for Physics

Text: Anna Davour

Translation: Clare Barnes

Illustrations: Johan Jarnestad

Editor: Sara Gustavsson

© The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

September/October 2025 Published on August 19, 2025

When Washington announced a “framework deal” with China in June, it marked a silent shifting of gears in the global political economy. This was not the beginning of U.S. President Donald Trump’s imagined epoch of “liberation” under unilateral American greatness or a return to the Biden administration’s dream of managed great-power rivalry. Instead, it was the true opening of the age of weaponized interdependence, in which the United States is discovering what it is like to have others do unto it as it has eagerly done unto others.

This new era will be shaped by weapons of economic and technological coercion—sanctions, supply chain attacks, and export measures—that repurpose the many points of control in the infrastructure that underpins the interdependent global economy. For over two decades, the United States has unilaterally weaponized these chokepoints in finance, information flows, and technology for strategic advantage. But market exchange has become hopelessly entangled with national security, and the United States must now defend its interests in a world in which other powers can leverage chokepoints of their own.

That is why the Trump administration had to make a deal with China. Administration officials now acknowledge that they made concessions on semiconductor export controls in return for China’s easing restrictions on rare-earth minerals that were crippling the United States’ auto industry. U.S. companies that provide chip design software, such as Synopsys and Cadence, can once again sell their technology in China. This concession will help the Chinese semiconductor industry wriggle out of the bind it found itself in when the Biden administration started limiting China’s ability to build advanced semiconductors. And the U.S. firm Nvidia can again sell H20 chips for training artificial intelligence to Chinese customers.

In a little-noticed speech in June, Secretary of State Marco Rubio hinted at the administration’s reasoning. China had “cornered the market” for rare earths, putting the United States and the world in a “crunch,” he said. The administration had come to realize “that our industrial capability is deeply dependent on a number of potential adversary nation-states, including China, who can hold it over our head,” shifting the “nature of geopolitics,” in “one of the great challenges of the new century.”

Although Rubio emphasized self-reliance as a solution, the administration’s rush to make a deal demonstrates the limits of going it alone. The United States is ratcheting back its own threats to persuade adversaries not to cripple vital parts of the U.S. economy. Other powers, too, are struggling to figure out how to advance their interests in a world in which economic power and national security are merging, and economic and technological integration have turned from a promise to a threat.

Washington had to remake its national security state after other countries developed the atomic bomb; in a similar way, it will have to rebuild its economic security state for a world in which adversaries and allies can also weaponize interdependence. In short, economic weapons are proliferating just as nuclear weapons did, creating new dilemmas for the United States and other powers. China has adapted to this new world with remarkable speed; other powers, such as European countries, have struggled. All will have to update their strategic thinking about how their own doctrines and capabilities intersect with the doctrines and capabilities of other powers, and how businesses, which have their own interests and capabilities, will respond.

The problem for the United States is that the Trump administration is gutting the very resources that it needs to advance U.S. interests and protect against countermoves. In the nuclear age, the United States made historic investments in the institutions, infrastructure, and weapons systems that would propel it to long-term advantage. Now, the Trump administration seems to be actively undermining those sources of strength. As the administration goes blow for blow with the Chinese, it is ripping apart the systems of expertise necessary to navigate the complex trade offs that it faces. Every administration is forced to build the plane as it flies, but this is the first one to pull random parts from the engine at 30,000 feet.

As China rapidly adapts to the new realities of weaponized interdependence, it is building its own alternative “stack” of mutually reinforcing high-tech industries centered on the energy economy. Europe is floundering at the moment, but over time, it may also create its own alternative suite of technologies. The United States, uniquely, is flinging its institutional and technological advantages away. A failure by Washington to meet the changes in the international system will not only harm U.S. national interests but also threaten the long-term health of U.S. firms and the livelihoods of American citizens.

Weaponized interdependence is an unanticipated byproduct of the grand era of globalization that is drawing to a close. After the Cold War ended, businesses built an interdependent global economy on top of U.S.-centered infrastructure. The United States’ technological platforms—the Internet, e-commerce, and, later, social media—wove the world’s communications systems together. Global financial systems also combined thanks to dollar clearing, in which businesses directly or indirectly use U.S. dollars for international deals; correspondent banks that implement such transactions; and the SWIFT financial messaging network. U.S.-centered semiconductor manufacturing was spun out into a myriad of specialized processes across Europe and Asia, but key intellectual property, such as semiconductor software design, remained in the hands of a few U.S. companies. Each of these systems could be understood as its own “stack,” interconnected complexes of related technologies and services that came to reinforce one another, so that, for example, buying into the open Internet increasingly meant buying into U.S. platforms and e-commerce systems, too. At a time when geopolitics seemed the stuff of antiquated Cold War thrillers, few worried about becoming dependent on economic infrastructure provided by other countries.

That was a mistake for Washington’s adversaries and, eventually, for its allies, too. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the United States began using these systems to pursue terrorists and their backers. Over two decades of cumulative experimentation, U.S. authorities expanded their ambitions and reach. The United States graduated from exploiting financial chokepoints against terrorists to deploying sanctions to target banks and, in time, to cutting entire countries, such as Iran, out of the global financial system. The Internet was transformed into a global surveillance apparatus, allowing the United States to demand that platforms and search companies, which were regulated by U.S. authorities, hand over crucial strategic information on their worldwide users.

The infrastructure of economic interdependence was turned against both the United States’ enemies and its friends. When the first Trump administration pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which the United States and other major countries, including in Europe, had negotiated with Iran in 2015 to limit its nuclear program, the United States threatened to sanction Europeans who continued to do business with the Islamic Republic. European governments found themselves largely unable to protect their own companies against U.S. power.

This was the context in which we first wrote about weaponized interdependence in 2019. By that point, many of the most important economic networks underpinning globalization—communications, finance, production—had become so highly centralized that a small number of key firms and economic actors effectively controlled them. Governments that could assert authority over these firms, most notably the U.S. government, could tap them for information about their adversaries or exclude rivals from access to these vital points in the global economy. Over two decades, the United States had built institutions to assert and direct this authority in response to a series of particular crises.

Some of Trump’s senior officials happened on our academic research and, to our amazement, liked what they saw. According to the historian Chris Miller’s 2022 book, Chip War, when the administration wanted to squeeze the Chinese telecommunications manufacturer Huawei harder, one senior official seized on the idea of weaponized interdependence as a playbook to strengthen export controls against semiconductors, describing the concept as a “beautiful thing.”

Economic weapons are proliferating just as nuclear weapons did.

Our primary purpose, however, was to expose the ugly underbelly of such weaponization. The world that globalization made was not the flat landscape of peaceful market competition that its advocates had promised. Instead, it was riddled with hierarchy, power relations, and strategic vulnerabilities.

Moreover, it was fundamentally unstable. American actions would invite reactions by targets and counteractions by the United States. The biggest powers could play offense, looking for vulnerabilities that they, too, could exploit. Smaller powers might seek to use less accountable or transparent channels of exchange, effectively building dark spaces into the global economy. The more the United States turned interconnections against its adversaries, the more likely it was that these adversaries—and even allies—would disconnect, hide, or retaliate. As others weaponized interdependence, the connecting fabric of the global economy would be rewoven according to a new logic, creating a world based more on offense and defense than on common commercial interest.

U.S. President Joe Biden also used weaponization as an everyday tool of statecraft. His administration took Trump’s semiconductor export controls to a new level, deploying them first against Russia, in order to weaken Moscow’s weapons program, and then against China, denying Beijing access to the high-end semiconductors it needed to efficiently train artificial intelligence systems. According to The Washington Post, a document drafted by Biden administration officials intended to limit the use of sanctions to urgent national security problems inexorably shriveled from 40 pages to eight pages of toothless recommendations. One former official complained of a “relentless, never-ending, you-must-sanction-everybody-and-their-sister . . . system” that was “out of control.”

Similar worries plagued export controls. Policy experts warned that technology restrictions encouraged China to escape the grasp of the United States and develop its own ecosystem of advanced technologies. That did not stop the Biden administration, which in its final weeks announced an extraordinarily ambitious scheme to divide the entire world into three parts: the United States and a few of its closest friends as a chosen elite, the large majority of countries in the middle, and a small number of bitter adversaries at the bottom of the heap. Through export controls, the United States and its close partners would retain access to both the semiconductors used to train powerful AI and the most recent “weights”—the mathematical engines that drive frontier models—while denying them to U.S. adversaries and forcing most countries to sign up to general restrictions. If this worked, it would ensure a long-term American advantage in AI.

Although the Trump administration abandoned this grand technocratic master plan, it certainly has not abandoned the goal of U.S. dominance and control of chokepoints. The problem for the United States is that others are not sitting idly by. Instead, they are building the economic and institutional means to resist.

The weapons of interdependence have been proliferating for several years and are now being deployed to counter U.S. power. As China and the European Union began to understand their risks, they, too, tried to shore up their own vulnerabilities and perhaps take advantage of the vulnerabilities of others. For these great powers, as for the United States, simply identifying key economic chokepoints is not enough. It is also necessary to build the state apparatus that can gather sufficient information to grasp the immediate benefits and risks and then put that information to use. China’s approach is coming to fruition as it presses on the United States’ vulnerabilities to force it to the negotiating table. By contrast, Europe’s internal institutional weaknesses force it to vacillate, putting it in a dangerous position vis-à-vis the United States and China.

For China, the former U.S. National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden’s 2013 exposure of U.S. surveillance practices demonstrated both the reach of the United States and the mechanics of the new era. Previously, Beijing had viewed technological independence as an important long-term goal. After Snowden, it saw dependence on U.S. technology as an urgent short-term threat. As our work with the political scientists Yeling Tan and Mark Dallas has shown, articles in Chinese state media began to trumpet the crucial role of “information security” and “data sovereignty” to China’s national security.

The real wake-up call came when the first Trump administration threatened to cut off ZTE, a major Chinese telecommunications company, from access to U.S. technology and then weaponized export controls against Huawei, which the administration had come to see as an urgent threat to U.S. tech dominance and national security. Chinese state media began to focus on the risks posed by “chokepoints” and the need for “self-reliance.”

These fears translated into policy actions as the Chinese Communist Party developed a “whole-of-nation system” to secure China’s technological independence, calling for “breakthroughs in major ‘chokepoint’ technologies and products.” China also began to think about how it could better exploit its advantages in rare-earth mining and processing, where it had gained a stranglehold as U.S. and other companies fell out of the market. China’s power in this sector comes not from a simple monopoly over the minerals, which the country doesn’t fully possess, but from its domination of the economic and technological ecosystem necessary to extract and process them. Notably, these critical minerals are used for a variety of high-tech industrial purposes, including producing the specialized magnets that are crucial to cars, planes, and other sophisticated technologies.

China had already threatened to cut back its rare-earth supply to Japan during a 2010 territorial dispute, but it lacked the means to exploit this chokepoint systematically. After it woke up to the threat of the United States’ exploitation of chokepoints, China stole a page from the American playbook. In 2020, Beijing put in place an export control law that repurposed the basic elements of the U.S. system. This was followed in 2024 by new regulations restricting the export of dual-use items. In short order, China built a bureaucratic apparatus to turn chokepoints into practical leverage. China also realized that in a world of weaponized interdependence, power comes not from possessing substitutable commodities but from controlling the technological stack. Just as the United States restricted the export of chip manufacturing equipment and software, China forbade the export of equipment necessary to process rare earths. These complex regulatory systems provide China not only with greater control but also with crucial information about who is buying what, allowing it to target other countries’ pain points with greater finesse.

This is why American and European manufacturers found themselves in a bind this June. China did not use its new export control system simply to retaliate against Trump but to squeeze Europe and discourage it from siding with the United States. German car manufacturers such as Mercedes and BMW worried as much as their U.S. competitors that their production lines would grind to a halt without specialized magnets. When the United States and China first reached a provisional deal, Trump announced on Truth Social that “FULL MAGNETS, AND ANY NECESSARY RARE EARTHS, WILL BE SUPPLIED, UP FRONT, BY CHINA,” recognizing the urgency of the threat to the U.S. economy. China’s long-term problem is that its state is too powerful and too willing to intervene in the domestic economy for purely political purposes, hampering investment and potentially strangling innovation. Still, in the short term, it has built the critical capacity to reimpose controls as it deems necessary to resist further U.S. demands.

Whether Europe can withstand pressure from Beijing—and, for that matter, from Washington—remains an open question. Europe has many of the capacities of a geoeconomic superpower but lacks the institutional machinery to make use of them. The SWIFT system, after all, is based in Belgium, as is Euroclear, the settlement infrastructure for many euro-based assets. European companies—including the Dutch semiconductor lithography giant ASML, the German enterprise software firm SAP, and the Swedish 5G provider Ericsson—occupy key chokepoints in technology stacks. The European single market is by some measures the second largest in the world, potentially allowing it to squeeze companies that want to sell goods to European businesses and consumers.

But that would require Europe to build its own comprehensive suite of institutions and independent stack of technologies. That is unlikely to happen in the short to medium term, unless the nascent “EuroStack” project, which aims to secure Europe from foreign interference by building an independent information technology base, really takes off. Even though Europe woke up to the danger of weaponized interdependence during the first Trump administration, it quickly fell back asleep.

In fairness, the EU’s weaknesses also reflect its unique circumstances: it depends on an outside military patron. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has heightened Europe’s short-term dependence on the United States, even as European countries struggle to bolster their defensive capacities. The Biden administration put a friendly gloss on economic coercion, coordinating with European governments such as the Netherlands to limit exports of ASML’s machinery to China. At the same time, the United States provided Europe with the detailed intelligence that it needed to wield financial sanctions and export controls against Russia, obviating the need for Europe to develop its own abilities.

Europe’s lassitude is heightened by internal divisions. When China imposed a series of export restrictions on Lithuania to punish it for its political support of Taiwan in 2021, German companies pressed the Lithuanian government to de-escalate. Again and again, Europe’s response to the threat of Chinese economic coercion has been kneecapped by European companies desperate to maintain their access to Chinese markets. At the same time, measures to increase economic security are repeatedly watered down by EU member states or qualified by trade missions to Beijing, which are full of senior officials eager to make deals.

Most profoundly, Europe finds it nearly impossible to act coherently on economic security because its countries jealously retain individual control over national security, whereas the EU as a whole manages trade and key aspects of market regulation. There are many highly competent officials scattered throughout the European Commission’s trade directorate and the national capitals of member states but few ways for them to coordinate on large-scale actions combining economic instruments with national security objectives.

The result is that Europe has a profusion of economic security goals but lacks the means to achieve them. Although European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has warned of “the risk of weaponization of interdependencies,” and her commission has prepared a genuinely sophisticated strategy for European economic security, it doesn’t have the bureaucratic tools to deliver results. It has no equivalent of the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which is capable of gathering information and targeting measures against opponents, or of China’s new export control machinery.

One immediate test is whether Europe will use its purported big bazooka, the “anti-coercion instrument,” or let it rust into obsolescence. This complex legal mechanism—which allows the EU to respond to coercion through a broad set of tools, including limiting market access, foreign direct investment, and public procurement—is supposed to allow Brussels to retaliate against allies and adversaries. The instrument was conceived as a response to the threat of Trump’s first administration and hastily retrofitted to provide a means of pushing back against China.

From the beginning, however, European officials made it clear that they hoped they would never have to actually use the anti-coercion instrument, believing that its mere existence would be a sufficient deterrent. That has turned out to be a grave misjudgment. The anti-coercion instrument is encumbered with legalistic safeguards intended to ensure that the European Commission will not deploy it without sufficient approval from EU member states. Those safeguards make other powers such as China and the United States doubt that it will ever be used against them. Its lengthy deployment process will give them the opportunity they need to disarm any enforcement action, using threats and promises to mobilize internal opposition against it. As with earlier European efforts to block sanctions, China and the United States can usually bet on the EACO principle that “Europe Always Chickens Out” in geoeconomic confrontations. Europe lacks the information, institutional clout, and internal agreement to do much else.

The anti-coercion instrument is the exact opposite of the “Doomsday Machine” in the film Dr. Strangelove, the classic Cold War satire. That machine was a disaster because it automatically launched nuclear missiles in response to an attack but was kept a closely guarded secret until an attack was launched. In contrast, European officials talk incessantly about their doomsday device, but Europe’s adversaries feel sure that it will never be deployed; that certainty encourages them to coerce European companies and countries at their leisure.

Europe is hampered by structural weaknesses, but the United States’ difficulties largely result from its own choices. After decades of slowly building the complex machinery of economic warfare, the United States is ripping it apart.

This is in part an unintended consequence of domestic politics. The second Trump administration imposed a hiring freeze across the federal government, hitting many institutions including the Treasury’s Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, which oversees OFAC, and leaving key positions unfilled and departments understaffed. Initial budget proposals anticipate an overall reduction in funding for the office, even as the number of sanctions-related programs has continued to rise. Although U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has expressed support for his department’s Bureau of Industry and Security, which is chiefly responsible for export controls, the agency lost over a dozen employees as part of the government’s sweeping force reductions. OFAC and the BIS were never as all-seeing as their reputations suggested and sometimes made mistakes. Nonetheless, they provided Washington with an extraordinary edge. Other countries had no equivalent to OFAC’s maps of global finance or the detailed understanding of semiconductor supply chains developed by key officials on Biden’s National Security Council.

Such institutional decay is the inevitable consequence of Trumpism. In Trump’s eyes, all institutional restraints on his power are illegitimate. This has led to a large overhaul of the apparatus that has served to direct economic security decisions over the last decades. As the journalist Nahal Toosi has documented in Politico, the National Security Council, which is supposed to coordinate security policy across the federal government and agencies, has cut its staff by more than half. The State Department has been decimated by job cuts, while the traditional interagency process through which policy gets made and communicated has virtually disappeared, leaving officials in the dark over what is expected of them and allowing adventurous officials to fill the vacuum with their own uncoordinated initiatives. Instead, policy is centered on Trump himself and whoever has last talked to him in the uncontrolled cavalcade of visitors streaming through the Oval Office. As personalism replaces bureaucratic decision-making, short-term profit trumps long-term national interest.

This is leading to pushback from allies—and from U.S. courts. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney recently warned that “the United States is beginning to monetize its hegemony.” U.S. federal courts, which have long been exceedingly deferential to the executive when it comes to national security issues, may be having second thoughts. In May, the U.S. Court of International Trade issued a striking decision, holding that the United States had overstepped its authority when it invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—the legal bedrock for much of U.S. coercive power—to impose tariffs on Canada and Mexico. That decision has been appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, but the judgment is likely just the first of many challenges. Notably, the trade case resulted from a complaint filed by conservative and libertarian lawyers.

The Trump administration’s assault on state institutions is weakening the material sources of American power. Across core sectors—finance, technology, and energy—the administration is making the United States less central than it used to be. Trump and his allies are aggressively pushing cryptocurrencies, which are more opaque and less accountable than the traditional greenback, and forswearing enforcement actions against cryptocurrency platforms that enable sanctions evasion and money laundering. In April, the U.S. government lifted sanctions against Tornado Cash, a service that had laundered hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of stolen cryptocurrency for North Korea, according to the U.S. Department of Treasury. And the bipartisan American love affair with stablecoins, a kind of cryptocurrency, is pushing China and Europe to accelerate their efforts to develop alternative payment systems.

Economic interdependence has been turned against the United States.

In some instances, the Trump administration has reversed Biden’s policies and promoted the diffusion of previously controlled technology. In a remarkable deal with the United Arab Emirates, the Trump administration agreed to facilitate the massive expansion of data centers in the region using advanced U.S. semiconductors despite continued relations between the UAE and China and warnings from policy experts that the United States should not depend on the Middle East for AI.

Most recently, the spending bill that Trump and his congressional allies pushed through earlier this summer effectively cedes control of next-generation energy technology to China by doubling down on the carbon economy. Even as Washington works to counteract Chinese influence over critical minerals, it is eliminating measures aimed at minimizing U.S. dependence on Chinese supply chains in the crucial areas of renewable energy and battery development and radically defunding its investment in science. The result is that the United States will face the unenviable choice between relying on Chinese energy technology or trying its best to make do with the moribund technologies of an earlier age.

One might have expected that the United States would respond to the age of weaponized interdependence as it responded to the earlier era of nuclear proliferation: by recalibrating its long-term strategy, building the institutional capabilities necessary to make good policy, and strengthening its global position. Instead, it is placing its bets on short-term dealmaking, gutting institutional capacity to analyze information and coordinate policy, and poisoning the economic and technological hubs that it still controls.

This does not just affect Washington’s ability to coerce others; it also undermines the attractiveness of key U.S. economic platforms. The use of weaponized interdependence always exploited the advantages of the “American stack”: the mutually reinforcing suite of institutional and technological relationships that drew others into the United States’ orbit. When used wisely, weaponization advanced slowly and within boundaries that others could tolerate.

Now, however, the United States is spiraling into a rapid and uncontrollable drawdown of its assets, pursuing short-term goals at the expense of long-term objectives. It is increasingly using its tools in a haphazard way that invites miscalculations and unanticipated consequences. And it is doing so in a world in which other countries are not only developing their own capacities to punish the United States but also building technological stacks that may be more appealing to the world than the United States’. If China leaps ahead on energy technology, as seems likely, other countries are going to be pulled into its orbit. Dark warnings from the United States about the risks of dependence on China will ring hollow to countries that are all too aware of how willing the United States is to weaponize interdependence for its own selfish purposes.

In the first decades of the nuclear age, American policymakers faced enormous uncertainty about how to achieve stability and peace. That led them to make major investments in institutions and strategic doctrines that could prevent nightmare scenarios. Washington, now entering a similar moment in the age of weaponized interdependence, finds itself in a particularly precarious position.

The current U.S. administration recognizes that the United States is not only able to exploit others’ economic vulnerabilities but also deeply vulnerable itself. Addressing these problems, however, would require the administration to act counter to Trump’s deepest instincts.

The main problem is that as national security and economic policy merge, governments have to deal with excruciatingly complex phenomena that are not under their control: global supply chains, international financial flows, and emerging technological systems. Nuclear doctrines focused on predicting a single adversary’s responses; today, when geopolitics is shaped in large part by weaponized interdependence, governments must navigate a terrain with many more players, figuring out how to redirect private-sector supply chains in directions that do not hurt themselves while anticipating the responses of a multitude of governmental and

nongovernmental actors.

Making the United States capable of holding its own in the age of weaponized interdependence will require more than just halting the rapid, unscheduled disassembly of the bureaucratic structures that constrain seat-of-the-pants policymaking and self-dealing. Successful strategy in an age of weaponized interdependence requires building up these very institutions to make them more flexible and more capable of developing the deep expertise that is needed to understand an enormously complex world in which Washington’s adversaries now hold many of the cards. That may be a difficult sell for a political system that has come to see expertise as a dirty word, but it is vitally necessary to preserve the national interest.

China built a bureaucratic apparatus to turn chokepoints into practical leverage.

Washington has focused more on thinking about how best to use these weapons than on when they ought not be used. Other countries have been willing to rely on U.S. technological and financial infrastructure despite the risks because they perceived the United States as a government whose self-interest was constrained, at least to some extent, by the rule of law and a willingness to consider the interests of its allies. That calculus has shifted, likely irreversibly, as the second Trump administration has made it clear that it views the countries that the United States has historically been closest to less as allies than as vassal states. Without clear and enforceable limits on U.S. coercion, the most dominant U.S.-based multinational firms, such as Google and J. P. Morgan, will find themselves trapped in the no man’s land of a new war zone, taking incoming fire from all sides. As countries work to insulate themselves from U.S. coercion (and American infrastructure), global markets are experiencing deep fragmentation and fracturing. There is “a growing acceptance of fragmentation” in the global economy, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has warned, and “maybe even more troubling—I think there’s a growing sense that ours may not be the best fragment to be associated with.”

That, in turn, suggests a deeper lesson. The United States benefited from its ability to weaponize interdependence over the last quarter century. It enjoyed the advantages of an international economy based on multilateral institutions and a technological regime built around its self-image as a liberal power, even while acting in unilateral and sometimes illiberal ways to secure its interests as it saw fit. Just a year ago, some American intellectuals and policymakers hoped that this system could survive into the indefinite future, so that unilateral U.S. coercive strength and liberal values would continue to go hand in hand.

That now seems extremely unlikely. The United States is faced with a choice: a world in which aggressive American coercion and U.S. hegemonic decline reinforce each other or one in which Washington realigns itself with other liberal-minded countries by forswearing the abuse of its unilateral powers. Not too long ago, American officials and many intellectuals perceived the age of weaponized interdependence and the age of American hegemony as one and the same. Such assumptions now seem outdated, as other countries gain these weapons, too. As during the nuclear era, the United States needs to turn away from unilateralism, toward détente and arms control, and, perhaps in the very long term, toward rebuilding an interdependent global economy on more robust foundations. A failure to do so will put both American security and American prosperity at risk.

India and EU strike landmark trade deal after two decades of talks January 27, 2026 Jamie Young ...