Why Greenland Is Of Growing Strategic Significance

Donald Trump seems more insistent than ever on controlling Greenland, but regardless of his controversial intentions, the island is of real strategic importance

Thomas Newdick THE WAR ZONE

Donald Trump wouldn’t categorically rule out using the U.S. military to take control of Greenland, saying that America needs it — as well as the Panama Canal — for “economic security.” Amid intense kickback from Denmark — a NATO ally of which Greenland is an autonomous territory — and other countries, it’s worth looking in more detail at the significance of the island, which is one of the world’s largest, in economic, geostrategic, and, above all, military terms.

Trump’s interest in Greenland has made headlines in recent days, although his designs on the territory are far from new. Back in 2019, TWZ reported on then President Trump’s claim that his administration was considering attempting to purchase Greenland from Denmark, the U.S. leader noting at the time that the idea was “strategically interesting.”

Since then, Trump’s territorial ambitions for Greenland (and elsewhere) have been ramped up several notches.

Speaking at a press conference yesterday, the incoming U.S. president refused to rule out military or economic coercion to bring Greenland and the Panama Canal under U.S. control.

“I can’t assure you on either of those two,” Trump told reporters. “But I can say this, we need them for economic security.”

The same day, Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr., touched down in Greenland for what was described as a tourist visit, during which he reportedly handed out hats bearing the slogan ‘Make Greenland Great Again.’

Talking about Greenland specifically, Trump threatened economic retaliation against Denmark, should the Scandinavian country — a NATO member — stand in the way of his territorial ambitions. Faced with such resistance, the United States “would tariff Denmark at a very high level,” Trump said.

Similar threats were leveled at Canada, too, where Trump said he would not rule out using “economic force” to turn America’s northern neighbor into a U.S. state.

In Denmark, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen yesterday ruled out the possibility of coming to a deal with the United States that would see Greenland handed over. Instead, the future of the territory would be decided by its people. “Greenland is not for sale,” Frederiksen said.

As to what the United States would be acquiring, should it somehow take control of Greenland, by whatever means, this territory is undoubtedly unique, and it’s also at the center of an increasingly strategic race to expand control and military influence across the Arctic region.

With Russia actively building up its military footprint in the wider region, it’s worth recalling that the United States already operates one of its most strategic military outposts in Greenland. Indeed, the U.S. military has for the better part of a century had a major military presence in Greenland, with the permission of the Danish government.

As we’ve explored in the past, the current relationship dates back to the early years of the Cold War, driven by the standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union and the enduring military significance of Greenland.

A U.S. military presence in Greenland can be traced back to before the superpower standoff, however. During World War II, when Denmark was under Nazi German occupation, an agreement was made with the Danish Ambassador to the United States that would allow the U.S. military to defend Danish settlements in Greenland from German forces, if required. After the German defeat, Denmark made efforts to remove the U.S. military presence but gave up once it joined NATO as a founding member in 1949.

From this point onward, the relatively short distance between Greenland and the communist foe meant that the territory was an ideal springboard for launching U.S. nuclear strikes on the Soviet Union, as well as for basing early warning radars and interceptor fighters that, in turn, could help counter a Soviet attack.

A year after the Alliance was established, the U.S. Air Force secretly began work on Thule Air Base in Greenland, which became the most significant military installation in the territory. Commencing operations in 1952, Thule Air Base was a critical installation during the Cold War, hosting Strategic Air Command bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, as well as interceptors and Nike nuclear-tipped surface-to-air missiles.

The Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) came to Greenland in 1961, when the BMEWS-Site 1 was established there, initially designated as the 12th Missile Warning Squadron and later the 12th Missile Warning Group. Air Force Space Command assumed control of Thule Air Base in 1983 and the unit was re-designated as the 12th Space Warning Squadron in 1992. In 1987, the BMEWS mechanical radar was upgraded to the more efficient and capable solid-state, phased-array system used today, the Upgraded Early Warning Radar (UEWR).

The Cold War years were turbulent ones for Greenland and Thule Air Base, and the outlying facilities saw more than their fair share of bizarre endeavors — as well as at least one incident that could have ended in nuclear catastrophe.

Between 1959 and 1967, the secretive Camp Century research facility, 150 miles east of Thule Air Base, conducted experiments in running military operations on the Greenland Ice Cap, which included a nuclear reactor below the ice. This also fed into Project Iceworm, a plan to construct a system of tunnels 2,500 miles in length, that could be used to launch 600 ‘Iceman’ missiles, modified two-stage Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), providing a ‘second-strike’ capability against the Soviet Union. You can read more about this outlandish unrealized scheme here.

Camp Century left a toxic legacy of buried weapons, sewage, fuel, and pollutants under the ice and there are potentially even more hazardous pollutants hidden here too, after Thule Air Base became the site of one of America’s worst nuclear accidents. In 1968, a cabin fire broke out in a B-52G bomber carrying four thermonuclear gravity bombs. The B-52 crashed onto sea ice in North Star Bay just west of the air base, with at least three of the weapons likely exploding on impact. Seven of the eight crewmembers survived the crash.

No nuclear detonations resulted, but the surrounding area was nonetheless covered with radioactive materials, while burning fuel and explosives melted the ice sheet, meaning that significant quantities of debris fell to the ocean floor. Project Crested Ice was launched to try and clean up the nuclear mess, although at least one of the thermonuclear weapons may still be unaccounted for. Until today, there are conflicting accounts of whether the entire bomb went missing, or whether it was a part of one of the fissile cores.

These incidents were somewhat forgotten after the end of the Cold War but have been brought back into focus as the Arctic ice continues to retreat under the effects of climate change.

Meanwhile, following its formal transfer to the U.S. Space Force in 2020, Thule Air Base was renamed Pituffik (pronounced bee-doo-FEEK) Space Base in 2023.

While the strategic significance of the air base waned after the end of the Cold War, the developing geopolitical situation in the Arctic has seen it become much more important again.

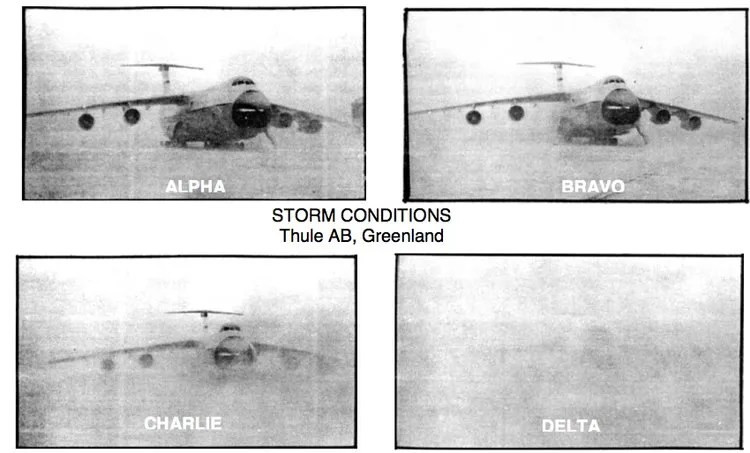

What hasn’t changed is the inhospitable nature of this remote operating environment, located well above the Arctic Circle and just 947 miles from the North Pole. In winter, temperatures here fall to as low as -47 degrees Fahrenheit while winds of up to 100 knots whip across the facility. Between November and February, the base is in constant darkness, while the sun never sets during the summer months of May to August.

Today, operations at Pituffik Space Base are overseen by the Space Force’s 821st Space Base Group, the mission of which is “to enable force projection, space superiority, and scientific research in the Arctic region for our nation and allies through integrated base support and defense operations,” according to the Space Force.

With Pituffik Space Base, the 821st Space Base Group is responsible for the U.S. military’s northernmost installation but also the world’s northernmost deep-water seaport, and a number of subordinate squadrons, as follows:

821st Support Squadron: provides mission support in the form of engineering, medical, communication, logistics, services, and airfield operations in support of the 821 Space Base Group and tenant organizations.

821st Security Forces Squadron: handles security of the 254-square-mile defense area in and around Pituffik. The area includes a ballistic missile early warning system, satellite control and tracking facilities, the air base, and the seaport that is only accessible for a short period during the summer. An annual sealift operation to support the base during this period is called Operation Pace Goose.

12th Space Warning Squadron: responsible for the AN/FPS-132 Upgraded Early Warning Radar (UEWR) system, a phased-array radar that detects and reports attack assessments of sea-launched and intercontinental ballistic missile threats heading toward North America. A secondary mission of the squadron is providing space surveillance data on satellites and other near-Earth objects like asteroids.

23rd Space Operations Squadron, Detachment 1: one of seven Remote Tracking Stations in the Satellite Control Network. Located approximately 3.5 miles northeast of the Pituffik main base, Det 1 provides telemetry, tracking, and command and control operations to the United States and allied government satellite programs.

While Pituffik is now primarily host to these various space and missile warning missions, fighter detachments are also making a comeback, reflecting one of the core Cold War missions for what was then still known as Thule Air Base.

Regular flying operations include Vigilant Shield, an annual, binational air defense training event staged with the Canadian military. In 2023, while it was still named Thule Air Base, the facility welcomed for the first time a detachment of U.S. Air Force F-35A stealth fighters, where they took part in a North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) exercise that you can read more about here.

Pituffik also regularly hosts surveillance missions, and scientific data-gathering flights, and serves as a hub for transports and search and rescue aircraft. It has an associated port facility that serves as a key logistics node.

The strategic value of Pituffik Space Base and its early warning mission means that it would be one of the first U.S. military installations to be targeted in the event of a nuclear exchange with Russia.

While such a scenario was part of the everyday Cold War reality, it’s something that appears more possible as Greenland again finds itself in the middle of another standoff between East and West.

In some respects, Trump’s preoccupation with Greenland reflects the degree to which the United States has, in recent years, lagged far behind Russia when it comes to establishing a more permanent footprint above the Arctic Circle — let alone in terms of more temporary operations in the region.

Meanwhile, Russia has placed a huge strategic importance on the Arctic, with many investments in the region. In recent years, Moscow has been heavily committed to increasing its air and naval power in the Arctic Circle and has been establishing new bases in the region, as well as reactivating ones that fell into disuse after the Cold War.

For some years now, Russia has enjoyed access to more than 50 airfields and ports in the Arctic region, from where it is able to project air and naval power that could deny the United States and its allies access to the Arctic. Russian maritime activity in the region is also enabled to a significant degree by a large and growing fleet of icebreakers, which dwarfs those used by the United States and its allies combined.

If anything, the strategic importance of the Arctic region as a whole has the potential to be a good deal greater than it was during the decades of superpower standoff, driven by climate change opening up new shipping routes as well as providing access to natural resources that were previously inaccessible, or at least much harder to exploit.

The importance of new shipping routes shouldn’t be underestimated. After all, whoever is able to control new lanes for commercial shipping and maritime traffic between Asian markets and Europe and North America will be able to dictate the terms of international trade in the Arctic.

While the Cold War rendered the Arctic a critical zone in terms of military strategy, the continued retreat of the sea ice in the region means that it is becoming increasingly important for economic development. Having maritime commerce traverse the Arctic will slash the journey times and costs of moving goods around the northern hemisphere. Meanwhile, resources in the wider region should provide new opportunities for undersea oil drilling, the mining of rare earth metals from the sea floor, and access to lucrative fisheries, to name just a few.

It’s therefore no surprise that the leading powers are now jostling for a position in the Arctic, with a military presence seen as vital to secure strategic access and natural resources.

NATO — including the United States, Canada, and Denmark — has long identified the Arctic as a region of “great power competition.” This rivalry now includes not only NATO and Russia but increasingly China, too.

With an eye on new shipping routes and natural resources, Beijing has been expanding its presence in the Arctic, and, in response to this, the Pentagon has defined the Arctic as “an increasingly competitive domain,” issuing specific warnings about China’s growing interest in the Arctic, including Greenland.

The Pentagon is also increasingly worried that, despite the potential for competition between them, China and Russia could cooperate on an Arctic strategy to the detriment of the United States. Indeed, major military cooperation already exists between China and Russia, especially in the naval space — and with a unique emphasis on the Arctic.

There’s little doubt that the geopolitical importance of the Arctic — and with it, Greenland — is only set to increase.

Thanks to its geographic location, Greenland is already of critical importance to the United States. Not only does the country’s security rely to a significant degree on missile detection and tracking capabilities in Greenland, but having a military foothold here provides unrivaled access to the Arctic, in the sea and air domains.

Were the United States to control Greenland or at least have greater freedom to expand its military presence there, it would be a logical outpost from which it could challenge Russia and China in the region. At the very least, its potential as a major logistics hub could be further enhanced, allowing the U.S. military to extend its reach further over the Arctic.

Alongside its support and surveillance functions, Greenland already provides the U.S. military with a logistics staging post, but it could also accommodate new command and control capabilities. Potentially, it could see a return to the basing of U.S. Air Force bombers and fighters, even on a permanent basis, if this is judged necessary. Echoing the previous practices, it could be used once again to station air defenses, to provide a forward line of defense against Russian bombers and missiles, although these could now include ballistic ones. There is even the possibility that the United States might choose to have long-range ground-based strike capabilities in Greenland, a Cold War throwback that is already poised to return to Western Europe, albeit in the form of conventional and not nuclear-armed missiles. Expanded port access in Greenland would also provide valuable and highly strategic maritime power projection points into the Arctic, as well as the North Atlantic. Those ports could be especially useful as operating locations for icebreakers.

A reinforced U.S. military presence in Greenland would very likely also address capabilities for a potential land war with Russia here and in the wider region. Due to its geographical position and its extremely limited means of repelling a ground invasion, Greenland is today considered a soft target by some. This is compounded by the fact that, while the U.S. Army is only slowly returning to more robust preparations for warfare in Arctic conditions, Russia is far more capable of fighting in northern latitudes and is introducing a variety of weapons systems that are optimized for this kind of environment.

One more legacy of the Cold War that has made a resurgence in recent years is Russian submarine operations, with a focus on the Arctic and North Atlantic, with Greenland in a highly strategic position. The vital Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom Gap, better known as the GIUK Gap, is a critical bottleneck through which Russian (and before them Soviet) submarines need to pass to effectively patrol the North Atlantic. During the Cold War, a significant portion of NATO naval power in Europe was dedicated to closely monitoring the GIUK Gap, and hunting submarines would have been a top priority in wartime. With Russia operating increasingly capable submarines, the GIUK Gap is once again of fundamental importance, and having anti-submarine warfare capabilities in Greenland would further bolster this effort.

So far, the United States has relied on cooperation with the Danish government to ensure that it retains a significant foothold in Greenland. Although this hasn’t always been entirely without problems, Denmark and the United States — as NATO members — have broadly aligned interests in the region, officially at least. Conceivably, the United States could potentially accomplish most of its strategic aims in Greenland via this same relationship, rather than taking over the island and claiming ownership of it.

Already today, it seems the Pentagon was seeking to distance itself from a potential seizure of Greenland. At a press conference, U.S. Department of Defense spokesperson Sabrina Singh said she was not aware of any draft of military plans for a Greenland invasion, and said that the department is focused on more immediate matters. “We’re concerned with the real national security concerns that confront this building every single day,” she said.

It remains to be seen whether the looming military competition in the Arctic region and the drive to compete with Russia and China in this remote corner of the world means that Greenland remains in Trump’s sights during his second term in office. Regardless, the potential for Greenland as a cornerstone of America’s military strategy in the Arctic is clear, whatever form that takes.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com